A Land of the Dead

With its land cutover, burned and abandoned, is it any wonder Wisconsin is full of ghosts?

Wisconsin's a land of the dead. Folklorist Robert Gard once mused that Wisconsin has more ghosts per square mile than any other state in the nation — if the stories are to be believed, that is. And he may not be wrong.

"Wisconsin Lore," authored by Gard and L.G. Sorden, opens with a 46-page chapter dedicated solely to ghost stories, though more can be found scattered throughout other chapters of the book.

Sometimes these stories are of entirely haunted swatches of land. Such is the case of The Haunted Grove, once located off Highway 18 but long since razed. For those who had to traverse the grove at night, they did so with great speed to avoid the area's otherworldly residents. One person, whose name is lost to history, reported being run down by a mad phantom driving a team of black horses hitched to a great, black carriage, which passed over him without a scratch.

Later, travelers through the grove would report run-ins with a strange, white creature that darted between their horse's legs and chased alongside them. Riders would also report the grove becoming filled with disembodied wails.

Turning to "The Wisconsin Road Guide to Haunted Locations," authors Chad Lewis and Terry Fisk fill 256 pages worth of haunted highways, landscapes and more. The book lists shadowy figures in Nekoosa and haunted hitchhikers in Baraboo, to name a few.

Not all of the state's haunts are outright frightening. More humorous than hair-raising are the ghosts of Chicken Alley in Maple Grove. Witnesses to the alley's hauntings report seeing spectral chickens distinguishable from their living counterparts due to their see-through nature. Others say that ghostly voices will warn those on foot off the road, and reports of will-o'-the-wisps are also not uncommon.

Even the plants lining the alley seem to belong to the other side. Some have claimed to see a large, disfigured tree along the roadside at night, only for it to be gone come daylight.

What binds these Badger State phantoms to the land? Trauma is the classic culprit as to why the spirits of the dead linger in the land of the living. The murdered seeking revenge on their murderer or even the trauma of a natural, albeit unexpected, end can be enough to keep the deceased from moving on — if, again, the stories are to be believed.

This would then suggest Wisconsin's people are easily or overly traumatized if they leave behind enough ghosts to dwarf the rest of the country. Yet, the state's early immigrants were the likes of lumberjacks, miners and farmers. Each required a certain level of hardiness to perform that doesn't lend itself to supporting the traumatized dead theory too well. In fact, some might have preferred death to felling trees in the frozen Northwoods of the state or toiling deep beneath its ground.

What if then it's not personal trauma that causes the state's haunts to hang around, but that the state itself — Wisconsin's ground — is traumatized?

Felling Trees, Moving Earth

Wisconsin is well-known for its forests, but what's seen today is relatively new in the grand scheme of the state's history. Long before it was famous for dairy cows and binge drinking, logging was Wisconsin's leading industry. Per the Wisconsin Historical Society, by the late 19th century, Wisconsin was one of the premier lumber-producing states in the country.

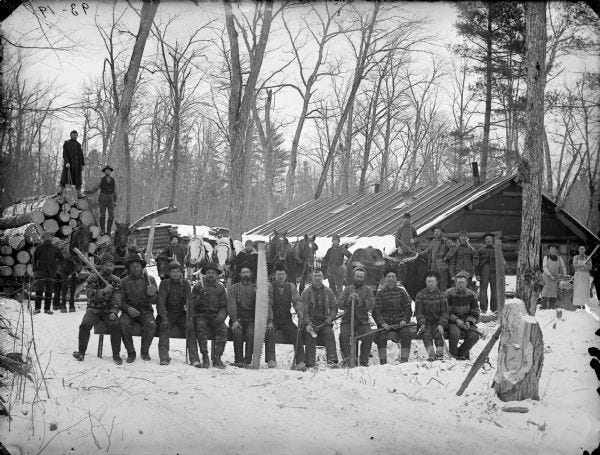

"According to the 1890 U.S. census, more than 23,000 men worked in Wisconsin's logging industry and another 32,000 worked at the sawmills that turned timber into boards. Each winter, the lumberjacks occupied nearly 450 logging camps. In the spring, they drove their timber downstream to more than 1,000 mills. Logging and lumbering employed a quarter of all Wisconsinites working in the 1890s," the Historical Society details.

The state's river system — chiefly the Wisconsin River, a tributary of the Mississippi River — made it possible to transport the logs from the woods to sawmills. As such, many logging towns and operations were situated near or with easy access to waterways. Then, with the advent of the railroad at the turn of the 20th century, the rivers were no longer as needed and logging operations could go wider and deeper in the state's forests.

As the Historical Society explains: "The soft pine forests of northern and central Wisconsin provided a seemingly endless supply of raw material to urban markets. Wisconsin trees were made into doors, window sashes, furniture, beams and shipping boxes. They were built in lakefront cities such as Sheboygan, Manitowoc and Milwaukee. Wisconsin lumber was used to construct buildings and houses for the Midwest's growing cities."

New technology also made it possible to expand logging operations in other ways. The Historical Society notes that while early logging operations had cut the most usable and profitable timber, new methods cleared entire forests, even revisiting areas that had already been logged.

Today, less than 1% of old-growth forest remains in Wisconsin, according to the Northwoods Land Trust.

With the forests cut to near-total depletion, the state and federal governments turned toward agriculture as a way to attract new residents to the state. They saw the cutover forests as opportune farmland. However, due to the often sandy soil that composed these lands, farming turned out to be a nonstarter.

"For the most part, that effort [farming] failed in the northern half of the state. Because of this, landowners couldn't pay their taxes and ended up abandoning their lands. This left the counties cash poor because they relied on those property taxes to pay for all the work expanding the road networks, building schools and paying their own taxes to the state. By 1927, over 4.5 million acres had become tax delinquent at least once," the Wisconsin County Forests Association details.

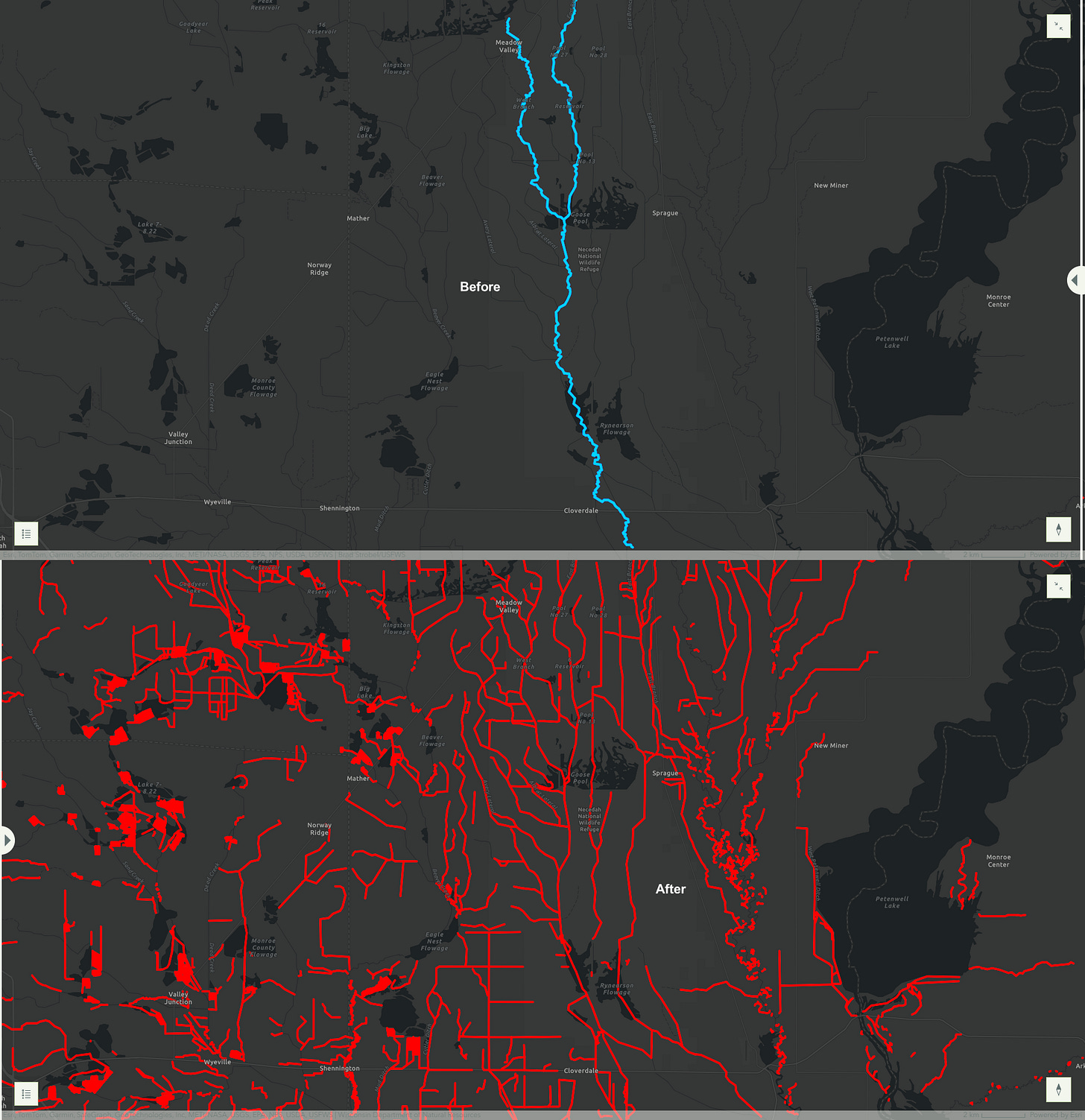

Though, this failure was not for a lack of trying. Settlers burnt the land to clear it for their farms, and entirely new drainage systems and waterways were constructed to feed them. Tons of earth was moved to reshape these river systems. The Little Yellow River is a prime example of a watershed and ecosystem remade for farming, with work ongoing to restore its natural configuration.

A Haunting Past

Currently, work is underway to restore and undo some of this damage. The Wisconsin DNR's reforestation efforts provide and guide landowners with the means to grow and tend to their woodlands, as well as steward the state-owned forests. And while the state still produces timber, they do so now with sustainable forestry practices.

Wisconsin is also part of the Trillion Trees Pledge. Governor Tony Evers signed an executive order on Earth Day, 2021, "pledging to protect and restore Wisconsin's forestland by conserving 125,000 acres and planting 75 million trees by 2030." He then upped that pledge to 100 million trees last year. As of this writing, the DNR says 32,098,500 trees have been planted as part of the initiative.

However, the land is old and its scars run deep — some permanent. If it can remember what was once inflicted on it, it almost certainly does. So, with its forests cut over, lands burned and rivers forcibly rerouted, perhaps it's no wonder Wisconsin's ground clings to everything it can — even the dead.